About Méabh Breathnach:

Through sculptural installations of objects in ceramics, metal and textiles, Méabh’s work questions where objects come from and what objects mean; the processes, the crafts, the people and the stories behind them. By subtly or dramatically changing the materials of these objects she attempts to expose and change the narratives that they tell, questioning what is aesthetically beautiful and valuable by using various skills to cast objects in different roles, ‘transforming ephemeral memories into crystallised objects, making the historic intimate and the scientific fallible’. Méabh exhibited in the Royal Scottish Academy’s New Contemporaries exhibition 2020, where she was awarded the Sir William Gillies Bequest.

VL – You exhibited two series of work in Disagio, Belly-Button bowls and The Towels. The former is an artwork that you came prepared to make before you arrived, the other a product of your residency experience. Can you tell me about the belly buttons and where that idea came from?

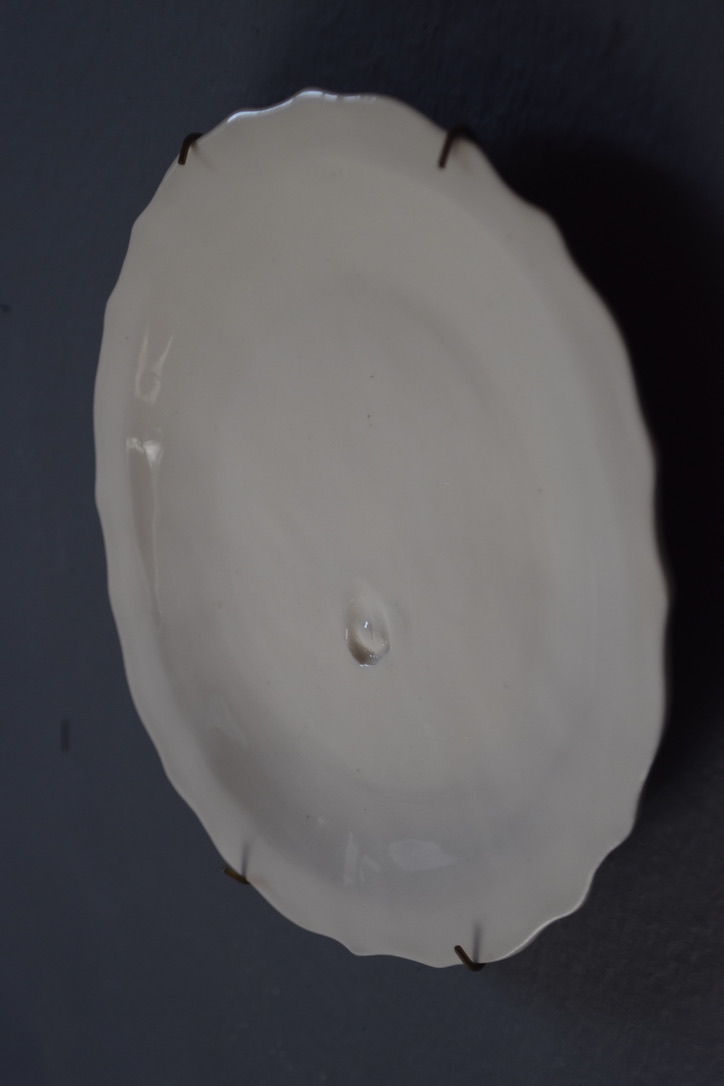

MB – My work always comes from process – and its history. I have always looked at traditional pottery shapes which are so bodily in form. I began to think of the body as being a vessel. I took traditional vase shapes and was interested in giving them body inclusions.

The shapes that reminded me of the stomach got belly buttons. There’s a subtlety to them – people don’t realise their eating of a belly – from afar they look serious – drawing on their object history – so there’s an element of humour that comes from a gentle digressing from this tradition. Humour is so important. I like the idea of giving people a comedic break from the anxiety we have about bodies – when they’re really just these silly fleshy vessels that take us through life. The belly buttons are tricks of the eye that discombobulate – a reminder of our own bodies in space and how they interact with art.

Taking art out of this super conceptual space reminds us that we need our bodies to experience them.

VL – Where do you get your body parts?

MB – I used to take metal casts of my body and displace them, setting them in surreal and uncomfortable settings. There’s an uncanniness to these permanent records of body parts that belong to a body that is always changing and from which they’re now detached.

VL – You’ve been working with belly button moulds here that you brought with you, how has the work changed over your time at Villa Lena?

MB – Being here where we’ve been eating communal meals made me want to impress them on the Villa Lena plates and bowls. I made moulds to emulate the VL design and created sets of porcelain plates and bowls to be imprinted. Before they were objects that held stuff within whereas now they are objects that facilitate nourishment.

The belly button is lightly pressed into the bowls – it’s a trace of the mould not obvious when we first approach the object. I love that this reflects the nature of belly buttons – they have no function but are a trace of an organ that first nourished us. It first started with me and my mum and thinking about what connected us in the beginning. It’s a reminder of our first physical relationship; the one between child and mother.

I mainly take casts of loved ones willing to go through the casting process so bringing the belly button molds with me is comforting. I like having them with me. There’s many layers here, one that is bringing my creative genesis – the belly buttons of my family and loved ones that artistically brought me here – but also bringing their belly buttons as they are the people that physically brought me into the world.

Belly buttons are my portraiture – I find every single one fascinating because they are all different and their own world. I work physically and the idea of capturing a part of someone at a particular moment in time is important to me.

I guess there’s aspects of the death mask but inverted – belly buttons are kind of like a birth mask – they capture the moment we’re born and stay with us for our whole lives.

The midwife who cut mine also cut my brothers – my mum says that she took so much care with both of us as she knew it would be with us for ever – so when I look down and see mine it is someones creation – I guess that sort of happens in my own work too – there a collaboration between myself and many midwives – but at the end of the day it is just a belly button. That’s where the humour comes in as it can be over intellectualised but actually its this funny awkward part of our bodies.

VL – Speaking of collaboration, how has this group residency impacted your work?

MB – I can’t be in a vacuum – I need the studio space that is a community where we exchange and feed each other’s practices. To have other artists here has given me so much confidence and encouragement – the meals here have been a coming together and sharing of creativity between artists. It’s from these moments that I decided to start imprinting on VL crockery.

There is you current cohort but also the artists that have come before you: that have used their space – how much of their presence/connection to them do you feel and how has that affected your time here

It’s amazing because there’s the obvious things like left over clay and tools but the kiln wasn’t properly cleaned and so left a black spot on one of the belly button pieces that looks exactly like a mole – and so now there’s this piece that i’ve made accidentally in collaboration with an anonymous artist from before me.

I like how much Villa Lena has either deliberately or accidentally shaped my work.

VL – On this theme, there are so many bodies here at the moment but also bodies that have been here before – what influence has that had?

MB – I like that this is a hotel and was thinking about the traces that guests and visitors leave with their bodies. Sheets and towels are washed but many people have slept in these beds before me, used these towels and these sheets – which connects us to these people we’ll never know or meet. I wanted to memorialise these liminal relationships so I found some old towels in the villa and soaked and shaped them in slip and fired them. The towels are the mold but evaporate in the firing process leaving only their shape – memorialising all the guests that have come before and to varying degrees left their mark on this place.

My work is about being a body and our relationship with the other. Be it old towels or belly buttons that are now repurposed allowing for other understandings of them as objects/flesh/body parts to come through.

VL – Is there an aspect of fetish here?

MB – I don’t think of my work as being particularly fetishising but undeniably there’s a sense of it because I deal with the body. I think it’s more that some people find their fetishes within it – as the body is where we experience sexuality. For me I’m much more interested in ‘the abject’. I’m excited by materiality and deliberately use materials that are associated with classic beauty/ high art – porcelain, red velvet, bronze – that have a sensuousness and particular tactility that have brought pleasure to peoples’ bodies. I guess if you combine this with body parts then maybe they can be sexualised but that’s not how I see them or set out to make them.

So much of the meaning of my work comes retrospectively – likewise with fetish – if they speak to certain fetishes there’s room within that for people to respond in that way.

VL – This brings us neatly to the group exhibition you all put on at the end of your residency which explored the theme of Disagio, how do you feel your works fitted into this?

MB – There’s an awkwardness I feel when prescribing meaning to my works, that I struggle with but accept. They have personal meaning to me, but I know that’s not necessarily for everyone, and I like that people have come away from them with completely different responses. That’s where disagio comes in – the abject is the closest word we have in English – the feeling of being made uncomfortable and icky and yet drawn in by it because there is something within it that’s meaningful, resonates, or is important.

Photographs by Lisa Mondiano

Méabh Breathnach is based in Glasgow, more info can be found about about her here

For more information about the residency and foundation see our website here